Digital vs Analog

From Francis Bacon to Modern Computers

People always think of digital technologies as being the cool, new kid on the block, but Francis Bacon, the scientific method fellow, worked out that two letters alone arranged in five ways can represent 32 different states. He then said,

any objects perceptive either to the eye or ear, provided only that those objects are capable of a twofold difference; as by Bells, by Trumpets, by Lights and Torches, by the report of Muskets, and any instruments of like nature.

Notice that proper nouns, like bell and trumpet, were capitalised in the olden days. That literary aside now out of the way, what did Bacon mean? He meant that two symbols can be communicated by a torch (on or off) or a trumpet (blowing or not blowing) and can be done so over a distance and, in the case of the torch, at the speed of light.

Bacon, in other words, spoke not only about digital codes, that is to say a set of arbitrary symbols that map to something else, but a binary code, as his alphabet contained only two symbols. Humans, he then realised, could broadcast these messages made up of just two symbols, regardless of the medium, over great distances. In this way, Bacon’s observation explains how the internet works, since information, from sounds to images, can be represented as zeros and ones and therefore be sent from one computer to another where they can be faithfully reconstructed.

Two centuries later, Morse took the idea of a two symbol code and built the first global-scale digital system that merged electromagnetism with the human mind. The telegraph proved Bacon right. The telegraph’s signals travelled close to the speed of light and did so across and eventually between continents. The operators at both ends encoded and decoded the digital signal, using Morse code, thus making them human computers. As I explain in Visionaries, Rebels and Machines, the telegraph went viral because the code, using Morse’s relay, were easy to amplify and, their killer use case, the coordination of trains, meant that wherever a railway ran so too could a telegraph line.

Bell Telephone Invention: From Telegraph to Harmonic Telegraph

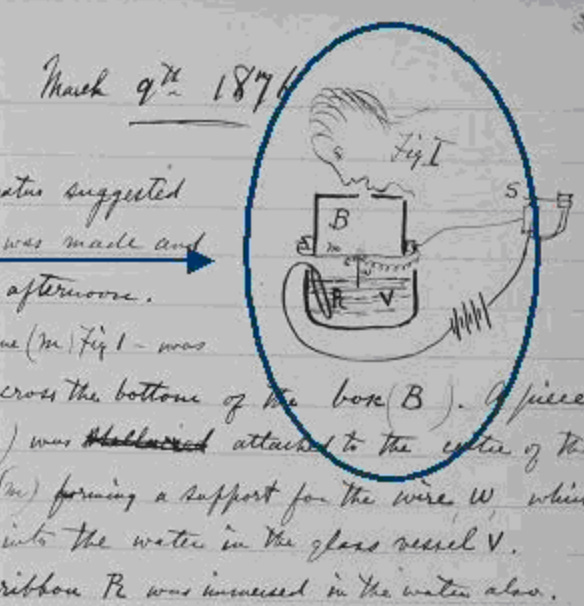

It did not happen immediately, because analog signals were hard to amplify, but Alexander Graham Bell arrived and thus the process of making digital technologies seem old hat arrived. With just one crucial change, Bell converted the telegraph into an analog machine that he called the harmonic telegraph. He replaced the telegraph key, the little device used for tapping out the dots and dashes, with a pin dangling off a diaphragm in a beaker of acidified water. Here is the sketch from Bell’s notepad from that fateful March in 1876, one hundred years before I was born and almost, to the day, 250 years after Bacon died:

The sound wave going into the diaphragm moved the pin in acidified water, ever so slightly. The tiny movements then altered the resistance of the circuit and thus created an electrical signal analogous to the sound wave that went into the diaphragm.

At the other end of the telegraph, Bell replaced the telegraph’s converter that punched out dots and dashes with a ‘speaker’ that converted the electrical signal to a sound wave by vibrating another diaphragm. In other words, the apparatus reversed the process of sound entering into the original diaphragm.

The harmonic telegraph became known as the ‘telephone’ from the Greek ‘tele’ for ‘distance’ and ‘phone’ for ‘sound’. The telephone, like other analog systems, did not require operators or codes as the message, nuances and all, survived the transformation process.

The fall and rise of digital technologies

Hot on the heels of the telephone came a slew of analog technologies. They included the phonograph, the cinema, radio and television and even practical tools such as radar. The Edison phonograph machine, as you’ll find out in a couple of episodes, scratched an analogue of sound waves onto tin foil. The camera captured moving pictures (the message) and stored them onto negatives on the film reel. The negatives were analogous to the message and used to recreate it when passed through another process and finally the projector which beamed the original images back to the screen like the phone ‘beamed’ the original sound wave back out of the speaker.

Cinema highlights the nature of analog systems; they provide an intuitive user experience, which explains why at the turn of the last century the future and all the cool tech was analog. This remained a fact of electronic life right up until the Second World War arrived and brought with it a use case suited to digital machines: the calculating of firing tables. Digital was back!

Once the firing tables were sorted, and after Oppie got busy in the desert, another use case arose: simulating nuclear explosions because blowing up actual bombs and the uranium in them was expensive. The nuclear age brought with it the rationale for research and development into digital and by that point electronic computing machines and began an long running relationship between the US Department of Defence and computer research. During these years, a reversal occurred and analog became old hat and digital was again the new kid on the block, despite been around since at least the time of Bacon.

Where to now?

Learning how the telephone grew out of the telegraph helps us to understand how technology evolves, itself a valuable lesson, but it also gives us the simplest comparison imaginable between analog and digital systems and signals—which most computer programmers, if they were being honest, find hard to explain.

Listen to the Bell episodes for more information and stay tuned as we start to piece together how the telegraph and the light bulb evolved to become the generative AI systems that are shaping our world today and how the study of zeros and ones evolved from Bacon’s musings into something called information theory.

Finally, read Chapter 6 if you really want to know more about Oppenheimer and how the work done out in Los Alamos is related to computers.

Digital vs Analog Signals: Definition

Digital signals use arbitrary symbols that map to something else through a code. Analog signals are directly analogous to the message they represent, like Bell’s electrical signal mirroring the sound wave.

Binary digital codes rely on just two symbols, like Bacon’s torches (on/off) or Morse’s dots and dashes.

An example of a non-binary digital code is the genetic code. There are four symbols in the code, Adenine [A], Thymine [T], Guanine [G] and Cytosine [C]. The four symbols make up words made of three symbols. CAT in this language maps to the amino acid Histidine like a three dots (…) map to S and three dashes (- - -) map to O in Morse.

Podcast links

Spotify:

YouTube: