Out of nowhere a voice boomed:

DON'T GIVE YOURSELVES TO THESE UNNATURAL MEN.

MACHINE MEN WITH MACHINE MINDS AND MACHINE HEARTS!

YOU ARE NOT MACHINES! YOU ARE NOT CATTLE!

YOU ARE MEN!

I spent a lot of time writing Visionaries, Rebels and Machines. To stay sane I needed different background music. Since 1996, my goto albums were Stanley Road, Jagged Little Pill and Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds but I needed a break so off I went, back in time, where on the way to the Pet Shop Boys the algorithm picked out Iron Sky by Paolo Nutini. The song builds to a crescendo and then boom, from nowhere a monologue like soft rain, mirroring the song, builds to its own climax right before Nutini flies back in with the last verse.

When that song echoed off my skull, after passing through my neural networks, two things came back with it. The first was the layered nature of innovation; ideas build on top of each other like that song is built on top of the YOU ARE NOT MACHINES monologue. The second was strategic inflection points, those points in the life of a business when everything changes, and if their leaders do not diagnose the change the business dies, usually quickly.

Layered Innovation

When I work with groups, to push people into a collaborative mode, I organise them into teams of three and ask the first person to draw a vehicle on a whiteboard. The second decorates the vehicle. The third augments it. Try it now. You might get something like this:

The end result, a rocket in this case, needed all three participants and none could have come up with that design on their own. I call this layered innovation but it’s naive to think just because the end results have obvious layers or components that that is how they were built; I doubt for example Paolo Nutini wrote that song, stuck the monologue in, and called it a day. He might have started with the monologue and worked backwards. He might have started with a different monologue. He might have written the song and found a monologue-sized hole in it. That rocket got its side thrusters last and then the second person came back in and drew the lightning bolts on them.

Strategic Inflection Points

Movies were silent until in the late 1920s. When they got sound, Harry Warner of Warner Brothers supposedly said, ‘Who the hell wants to hear actors talk’. In 1930, Charlie Chaplin said sound would destroy the nuances of his work as a mime. Chaplin refused to join the talking movies. In 1931 he appeared in the silent movie, City Lights. Five years later Chaplin starred in Modern Times, a movie with spoken parts but not for him.

It is natural but unfair of us to suggest Chaplin was stupid. In retrospect, history only ever takes one path, the path that was taken. This leads to the I-knew-it-all-along phenomenon which deceives us into thinking, in this example, that filmmakers would inevitably marry sound to vision and give us the movies we have today.

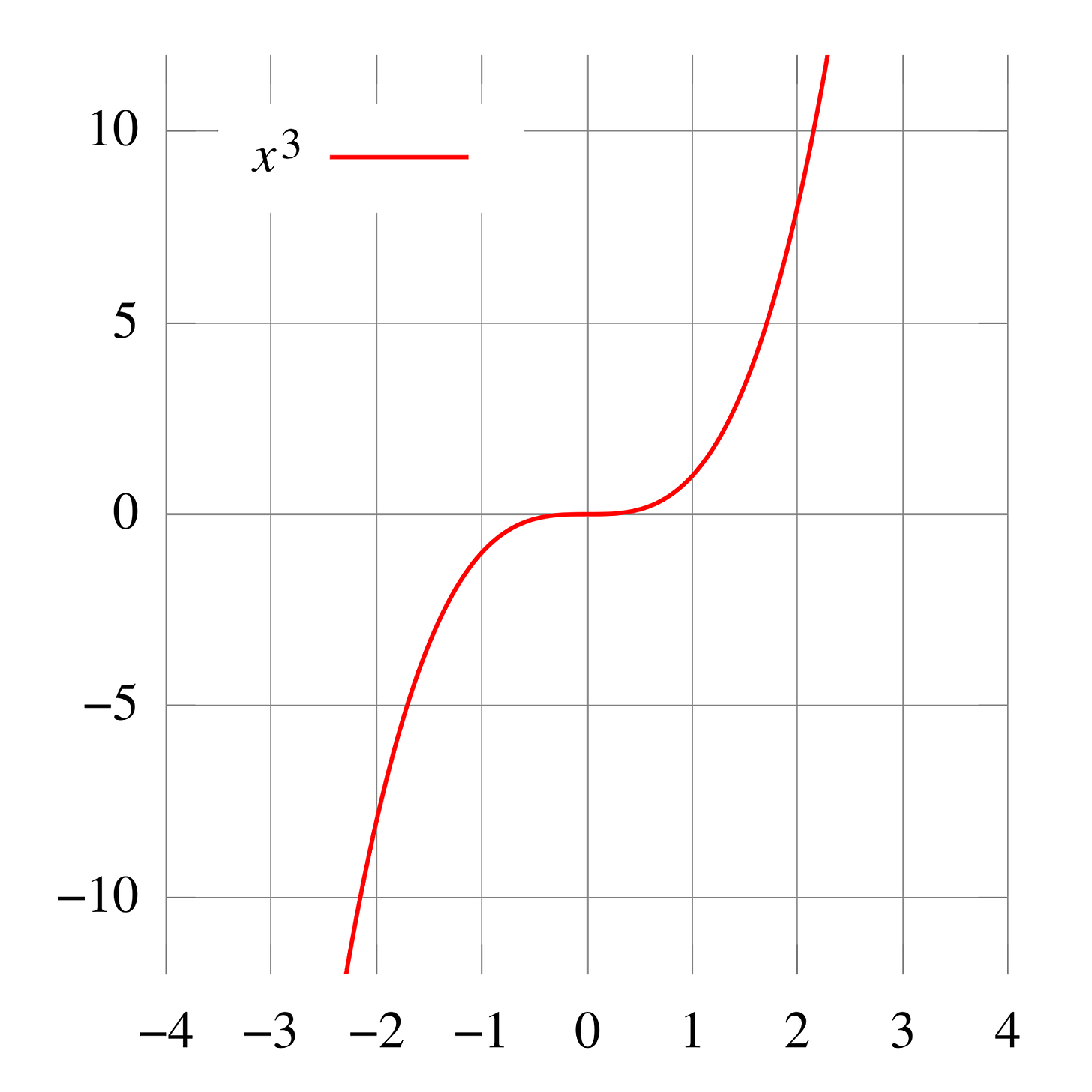

Charlie Chaplin passed through a strategic inflection point, a term repurposed from mathematics by Intel’s former CEO, Andy Grove, in his book, Only the Paranoid Survive.

A strategy inflection point is the moment the world flips upside down, like it did for Charlie Chaplin and Harry Warner in the 1930s. The rule of thumb with strategic inflection points is that without a fundamental change, the business dies. Those who recognise and then react to the inflection point win. Intel won when they navigated a strategic inflection point but only after the team fell into the same cognitive traps that Chaplin and Warner fell into.

Intel’s strategic inflection point

Andy Grove shuffled around for a year in shock. One day he walked into Gordon Moore’s office and said, ‘If we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO, what do you think he would do?’ Moore did not flinch. A new CEO would get them out of the memory business.

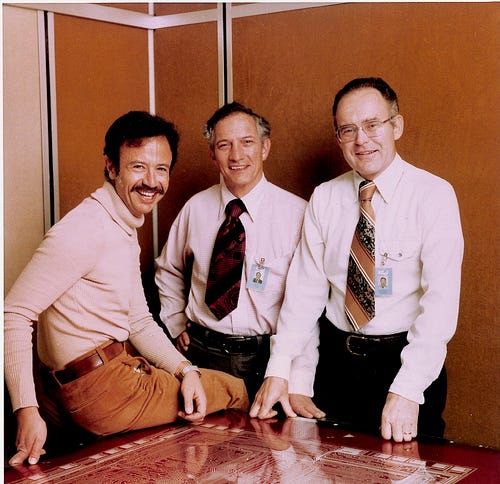

Less than 20 years earlier, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore built Intel around Moore’s 1965 observation that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every 18 months. If true, then by the time 1970 rolled around, it would be possible to manufacture large-scale integrated (LSI) circuits with more than a thousand components on them.

Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore bet on large-scale integrated circuits, they bet that semiconductors would soon be able to do things that were off limits and they bet that one of those things would be computer memory. In other words, they bet on the strategic inflection point they thought they were in the middle of.

As Noyce, Moore and Grove navigated this strategic inflection point, across the country in New York state, a young engineer called Steven Sasson experimented with a new invention called the charge-coupled device (CCD), an integrated circuit that senses light. He designed the CCD into a device with a lens for input, an algorithm that converted the light into numbers — and therefore digitised it — and a tape to output the reconstructed image. If the team at Intel continued to make Moore’s law a reality, this clunky device would not remain clunky for long. Sasson’s managers at Kodak laughed at him, filed a patent in 1978 and left him alone in a lab to tinker with his ‘digital’ camera.

As the 1970s came to an end, Intel owned computer memory after navigating a strategic inflection point. Unfortunately for them, the arrogance and wishful thinking of the old computer memory companies that Intel exploited, combined with an unexpected new source of wealth from microprocessors, blinded them to the next inflection point, the rise of Japanese computer memory.

The personal computer

In 1976, the two Steves launched Apple Computer. Mike Markkula, a former marketing manager at Intel and some say the world’s first angel investor, played tennis, built furniture, and, on Mondays, gave free advice to entrepreneurs. This is how he met Jobs and Wozniak.

Markkula contacted Noyce who arranged for a demonstration of Apple’s new-fangled personal computer to Intel’s board. With the expectation of Arthur Rock, the investor who set up Intel with Noyce and Moore, the board was not impressed. Intel passed on an investment in Apple but Rock later invested $60,000.

Rock and Markkula were not the only links between Intel and Apple. Ann Bowers left Intel after she married Noyce because she didn’t think it was appropriate to be married to the boss. As 1976 turned into 1977, Bowers set up a consultancy business and soon agreed to help Apple. In the process, Bowers bought some of Wozniak’s stock.

Bob thought Ann was nuts. He had an inkling that personal computers might one day be big, but there was no way these two hippies, aged 21 and 26, would be the ones to make them big. Wozniak, the phone phreaker, stole telephone calls with a device that emitted electronic pulses. Jobs had an unkempt beard, long hair and wore jeans and Birkenstocks. Somebody might one day make money with personal computers but it would not be these two. Noyce, Silicon Valley’s original rebel, the mould from which all others were cast, who once had the audacity to wear short-sleeved shirts to work, baulked at these two who didn’t even cut their hair. Ann, of course, saw past the sandals and long hair and in doing so saw what that the great predictor and shaper of the future, Robert Noyce, did not.

By 1980, Apple’s success proved Ann Bowers, Arthur Rock and Mike Markkula right. With the Steves, they had sensed a strategic inflection point, bet on it and helped to shape a winner.

The microprocessor

Robert Noyce first rose to fame when he had the idea to carve electronic components onto a block or chip of silicon. Instead of factory workers wiring circuits up by hand, a machine could now ‘print’ a conductor on top of the chip and its components. The printing of the conductor meant that integrated circuits or microchips, as they became known, could be manufactured at scale.

In 1969, Noyce was at it again. Under Bob’s guidance, the team at Intel invented a chip that executed computer programs stored on memory chips. Rather than load the program from a tape, a device with this new chip could, for example, load from computer memory a program that calculated logarithms. This chip, what some called a computer-on-a-chip, processed microcode and so became known as the microprocessor.

Chips like this get into products with a ‘design win’. Like when Sasson designed his digital camera around the charged coupling device, a design win happens when a manufacturer of chips, like Intel, convinces a company like Sony to design a product around one of their chips.

By the time 1979 rolled around, design wins for Intel’s 8086 microprocessor, which had evolved from the original they designed back in 1969, were few and far between. Motorola and their superior chip battered Intel.

Intel, however, thought they could beat Motorola in customer service. They conceived a sales and marketing initiative called Operation CRUSH. They would remind the market of just how good their service was and, while they were at it, double the number of design wins for the 8086. CRUSH resulted in a remarkable 2,500 design wins. None were more significant than Earl Whetstone’s.

Like many at Intel, under Grove’s guidance, Whetstone, a sales engineer, took risks. This is what he did when he asked for, and got, a meeting with IBM, the most successful computer company in the world and, at that time, the world’s biggest company.

The door opened for Whetstone because IBM needed an outside vendor to build a microprocessor for their upcoming line of personal computers. They had never done this before. IBM built proprietary and therefore impossible to clone products. In 1980, though, they were playing catch-up to that Californian pipsqueak.

Following the same logic, IBM also asked a software developer that specialised in microcode for microprocessors to write the operating system. The resulting personal computer brought together the hardware company, Intel, into a decades long association with a software development house called Microsoft. Unbeknown to all parties, the future architecture of personal computers had just been conceived.

IBM exchanged the heart and soul of their new machine, neither of which was proprietary, for a quicker time to market. They never recovered. Demand for IBM’s personal computer exploded. IBM’s competitors then cloned the machines and undercut them on price. Every clone had a microprocessor from Intel and an operating system from Microsoft.

The problem with profit

The profits from the sales of microprocessors masked the wave of Japanese memory that broke on Intel’s shores. As 1983 changed into 1984, Intel built more factories and hired more staff to meet the forecast demand. When the economy cooled, these actions proved premature and worse, impossible to reverse. At the same moment, the whole industry woke up to the fact that Japanese memory was better quality and cheaper. If Intel tried to fight this battle, it would be its last.

Who tightened the noose around Grove’s neck so that every year was harder to breathe in than the one before? The Japanese? The president and his Reaganomics? The up and down swings of capitalism? None of these things.

Where a person or company is on their journey dictates their response to strategic inflection points. If they are young, they are risk-seeking. If they have a global brand to protect, like Charlie Chaplin, or are dominant in one domain, like Intel and Kodak were, then they have a lot to lose and so become risk-averse. Between 1970 and 1980 Intel transformed from an open minded, plucky upstart into a closed minded and xenophobic stick-in-the-mud, joining IBM who reacted so slowly to the arrival of their own inflection point, the personal computer, that they made a decision they never recovered from.

This pattern of behaviour explains why Microsoft, the risk-seeking and plucky start up, swooped in and took advantage of the personal computer inflection point but only ten years later dismissed the internet and its killer app, the web, as a fad. In the same way Harry Warner spurned sound, Microsoft spurned the chance to move applications like Microsoft Word to the web and that meant they never grokked web-scale infrastructure like Google and Amazon did. Google’s Docs bit off a piece of Microsoft’s pie and Amazon scooped up 7 years of competition free business with Amazon Web Services.

Three predictable responses to strategic inflection points underly this behaviour.

Arrogance

As early as 1978, just after he relinquished day-to-day control, Robert Noyce warned Intel about Japanese memory. Like Sasson, who warned Kodak that Moore’s law would kick in at the exact moment their patent expired, Noyce was gifted with foresight but cursed not to be believed. Grove and Moore’s arrogance blinded them to Noyce’s warning.

Wilful ignorance

Whetstone’s win at IBM made Japanese memory (and Bob Noyce) easy to ignore. But microprocessors and computer memory were distinct businesses. There is no way that the numbers from those businesses were jumbled together or that Intel did not understand the tax windfall that came their way in 1982. Besides, we don’t have to speculate because in a frank admission in Only the Paranoid Survive, Grove said he attacked the data.

Denial

Despite the remarkable success of CRUSH, the full ramifications of which were in the future, Intel was a memory business. They lived, breathed and dreamed of computer memory. Their multi-billion-dollar manufacturing operation produced memory. Memory proved Noyce and Moore right. Memory propelled Intel to the stock market and made them both rich. But memory would take them no further. The team at Intel could not face that fact in 1980, 81, 82 and 83. By 1984, they had no choice.

The aftermath

Until his death, Grove spoke about the events of those years as if they were fresh in his memory. After he met Moore that day, he still could not say the words, ‘Intel is getting out of the memory business’. Eventually, the board voted to exit the memory business in what Arthur Rock said was the most ‘gut-wrenching’ decision he had ever made.

As Grove’s arrogance gave way to depression and then humility, three things dawned on him that returned in Only the Paranoid Survive as lessons for how Intel survived their strategic inflection point.

Firstly, after he spoke to Moore, Grove realised that an outsider’s perspective brought clear vision. Grove’s biographer, Tedlow, said he had an out of body experience that let him see clearly. Psychologists call this disassociation. Whatever the truth, it allowed Grove to see the situation clearly.

Secondly, Grove realised he had to tap deep emotional reserves. There he found the determination that pointed to a way out. Could Intel escape on the lifeboat of microprocessors?

The microprocessor had been shelved multiple times. Intel had no idea what to do with it but they kept it alive, hidden away not in Intel’s best labs, which were reserved for computer memory, but instead in a lab on the periphery.

Therefore the third realisation, something the Steves and Bill Gates had known for years, was that the personal computer was here to stay. If true, Intel’s way out was with microprocessors.

After being mute for over a year, Andy Grove found his voice and when started to organise Intel’s exit from the memory business. They would escape the tsunami of Japanese memory in a lifeboat of their creation: microprocessors.

How did they know? They didn’t.

Intel had no idea that they needed that particular lifeboat. They did not predict that Mike Markkula would leave Intel because Grove didn’t like him. They could not have predicted that IBM would break the only unbreakable rule they had: never outsource the core components of your product to an outside vendor. But by building up a microprocessor capability, they managed to prepare for the future they did not see coming.

Once Grove had let go of the past and let the future come in, Intel’s new strategy emerged. First of all, Intel perfected manufacturing. Secondly, they built on their strong marketing capability which gave us the ‘Intel Inside’ logo in 1991 and the Intel ‘bong’ in 1995. Finally, as the inventors of the microprocessor, they had a lead here that they doubled down on.

It is obvious in hindsight, as history’s path always is, that this strategic inflection point transformed Andy Grove who in turn transformed Intel. And that’s the real lesson. Businesses don’t change unless the people inside them change.

The End

Strategic inflection points come and go. Those who recognise and respond to them gain a competitive advantage. Microsoft took advantage of the personal computer strategic inflection point. They then saw but failed to react to the internet as the next inflection point and so a company with a search engine and another one that sold books beat them to the punch.

At around about the same time, Sasson’s remarkable prediction came to pass. Kodak had their lifeboat, digital cameras. Unlike Andy Grove at Intel, Kodak’s leadership could not find the outsiders’ perspective and strength to load their company onto the lifeboat of digital cameras and sail away. They filed for bankruptcy in 2012. We do not know if Intel will survive NVidia’s present onslaught.

Charlie Chaplin, like Andy Grove, finally accepted the future. In 1940, he scored a smash hit with his first speaking role in The Great Dictator. In the film, Charlie Chaplin delivers a devastating monologue, tearing down Hitler, fascism and the dark side of capitalism that enabled both. Breaking the fourth wall, he addresses the audience directly:

To those who can hear me, I say - do not despair.

The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed -

The bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress.

The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people.

And so long as men die, liberty will never perish.

DON'T GIVE YOURSELVES TO THESE UNNATURAL MEN.

MACHINE MEN WITH MACHINE MINDS AND MACHINE HEARTS!

YOU ARE NOT MACHINES! YOU ARE NOT CATTLE!

YOU ARE MEN!